Scientists rise up against statistical significance

Highlight

- There is many misinterpretation of p-value significance :

- The p-value does not calculate the chance of a phenomenon to exist.

- The p-value does not calculate the size of a phenomenon.

- The p-value does not tell if we can accept of reject a phenomenon.

- We should be careful not to treat P-values and confidence intervals as categorical values, like the dichotomisation as statistically significant or not.

Links

- A video introducing the topic video “La fiabilité des articles scientifiques, Hygiène Mentale & Zeste de Science, Le Vortex #15”.

- An example of platform to register studies : https://osf.io/

- Another interesting paper : “Model Evaluation, Model Selection, and Algorithm Selection in Machine Learning” lien

Introduction

The significant p-value is often misunderstood and misinterpreted. The starting thought of this paper is that we have all read on a paper that because a difference between two groups was statistically non significant, there was no effect or difference. This is a misconception of the interpretation of statistically significant or non-significant, as a reminder :

- a statistically non-significant result does not prove the null hypothesis.

- a statistically significant result does not prove some other hypothesis.

P-value

The null hypothesis is generally that there is no effect or no difference between groups. The alternative hypothesis is that there is a difference, this is the effect we are investigating. The p-value is based on the assumption that the null hypothesis is true. It tells us the probability of observing our data under that assumption.

The p-value is a probability and we can be wrong with the statement used. The p-value depends on the data and the assumptions of the test, it can lead to false conclusions.

A low p-value (like 0.05 or less) suggests that the observed data is unlikely under the null hypothesis, but it doesn’t prove that the null hypothesis is false, nor does it confirm the alternative hypothesis (the phenomenon investigated). It just indicates that the data is inconsistent with the null hypothesis.

Common misconceptions

- If the P-value is larger than a threshold like 0.05 (or other), and the confidence interval includes zero, we should not conclude that there is ‘no difference’ or ‘no association’.

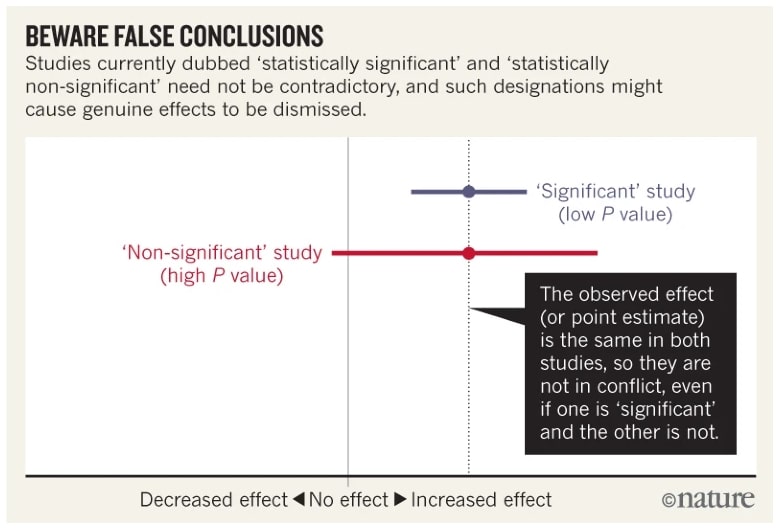

- Two studies are not necessarily in conflict because one has a result statistically significant and the other not.

- A p-value might be low simply due to a large sample size, not because the effect is important or real.

False conflict between paper

In this example there is two studies, they explore the unintended effect of an anti-inflammatory drug (atrial fibrillation risk, a disturbance of heart rhythm).

In this example there is two studies, they explore the unintended effect of an anti-inflammatory drug (atrial fibrillation risk, a disturbance of heart rhythm).

- The first study of Schmit et al.1 found a risk ratio of 1.2 with a 95% interval of confidence (1.09, 1.33). This study P-value was P= 0.0003 so the result are statistically significant.

- The second study study of Chao et al.2 found a risk ratio of 1.2 with a 95% interval of confidence (0.97, 1.48). This study P-value was P = 0.091 so the result are non statistically significant.

Because the second study’s result was not statistically significant, its authors concluded there was “no association” between the drug and the unintended effect, contrasting their findings with the statistically significant results of the first study. However, this reliance on the significance threshold is misleading.

When we compare the results, the first study is simply more precise, with a narrower confidence interval and a smaller P value. However, the two studies are not in conflict 3. The point estimates (1.2) are identical, and the confidence intervals overlap substantially, indicating compatibility between the studies. Authors should always discuss the point estimate, even if the P value is large or the interval is wide, and also address the interval’s limits.

Instead of framing their results as contradictory, the authors of the second study could have written: “Like the previous study, our results suggest a 20% increase in atrial fibrillation risk with anti-inflammatory drugs. However, based on our data and assumptions, the risk difference could range from a 3% decrease (a small negative association) to a 48% increase (a substantial positive association).” By discussing the point estimate, addressing the uncertainty in the confidence interval, and avoiding over-reliance on P values, authors can prevent false claims of “no difference” and overly confident conclusions.

False interpretation of “non-significance” into “no difference” or “no effect”

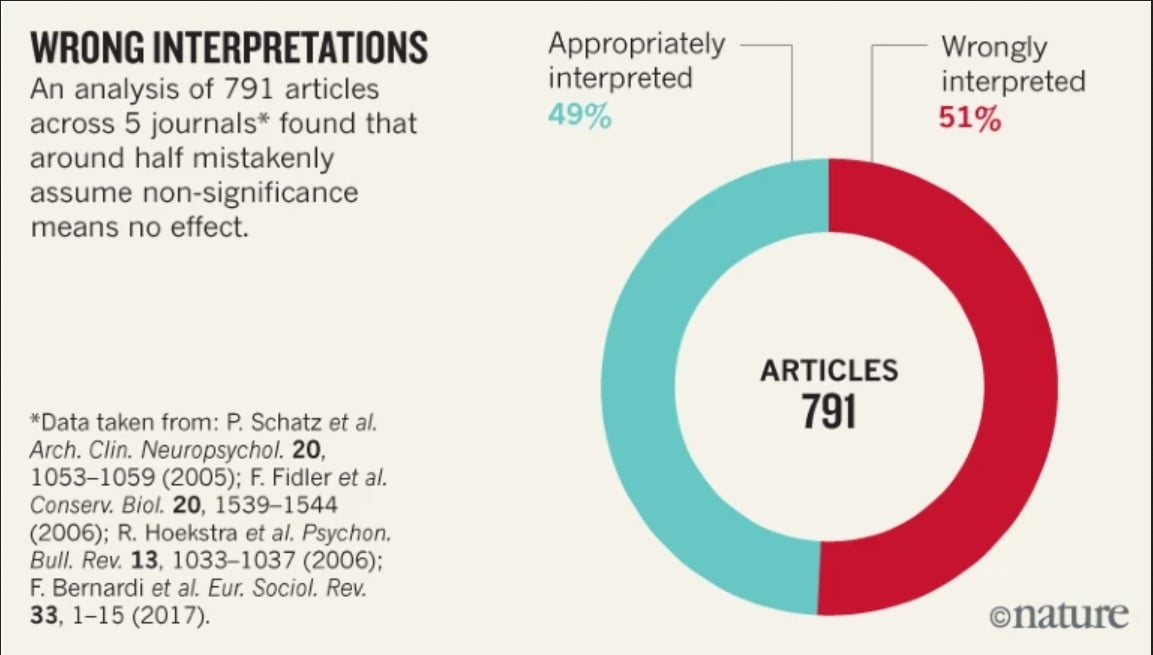

The problem with assigning results into ‘statistically significant’ or ‘statistically non significant’ is that it leads people to thinks that the results are categorically different. Moreover this focus on statistical significance pushes researchers to choose data or methods that gives statistical significance for some wanted/publishable result or that give non-significance for some unwanted ones (like drug side effects mentioned before), in the end it leads to making the conclusions unreliable. On 791 article 51% of the papers were wrongly interpreted with no significance as indicating ‘no difference or ‘no effect’.

The problem with assigning results into ‘statistically significant’ or ‘statistically non significant’ is that it leads people to thinks that the results are categorically different. Moreover this focus on statistical significance pushes researchers to choose data or methods that gives statistical significance for some wanted/publishable result or that give non-significance for some unwanted ones (like drug side effects mentioned before), in the end it leads to making the conclusions unreliable. On 791 article 51% of the papers were wrongly interpreted with no significance as indicating ‘no difference or ‘no effect’.

The paper advocates to stop using the concept of statistical significance. They do not advocate to ban the P-value, but rather to stop using the conventional dichotomous way to take the decision if a results refutes or supports an hypothesis.

A call for better science practice

They propose that the pre-registration of studies and the commitment to publish all analyses and results as a solution to reduce the reliance on ‘significance’. There still can be bias that can occur even with the best intention, but it is still better than to ignore the issue. Also we should interpret results broadly. It’s fine to suggest reasons for findings, but we should discuss multiple explanations, not just preferred ones. Focusing on factors like study design, data quality, and mechanisms, often matter more than P values or intervals.

An example of platform to register studies : https://osf.io/

Confidence Intervals

‘Confidence Intervals’ could be renamed as ‘compatibility intervals’ and we should be careful to avoid overconfidence when interpreting them. They recommend to focus on what all the values in the interval mean, by describing the implications of the observed effect and the limits. Given that all the values in the interval fit the data based on the assumptions, focusing on just one value, like the null, as “proven” is incorrect. An interval containing the null value often includes other values that could be highly significant. However, if all the values in the interval seem unimportant, you could conclude that the results suggest no meaningful effect.

So when discussing compatibility intervals, here is what they advise to keep in mind :

- Values outside the interval aren’t completely wrong : The interval shows the most compatible values, but values just outside it are still somewhat compatible and similar to those just inside. It’s wrong to say the interval includes all possible values.

- Not all values inside the interval are equally compatible :The point estimate is the most compatible, with values near it more compatible than those near the limits. Always discuss the point estimate, even with a large P value or wide interval, to avoid overconfidence or declaring “no difference.”

- The 95% standard is arbitrary (like the 0.05 threshold) :The default value isn’t absolute and can vary based on the situation. Treating it as a strict scientific rule can lead to problems, such as overemphasizing significance.

- Be humble about assumptions: Compatibility depends on statistical assumptions, which are often uncertain. Be clear about these assumptions, test them when possible, and report alternative models and results.

Retiring statistical significance

The main argument opposed to retiring statistical significance is the need of yes or no decisions. But for real-world decisions often required in regulatory, policy and business environments, it’s better to weigh costs, benefits, and probabilities rather than use yes-or-no thresholds. P values don’t predict future study outcomes reliably. By retiring statistical significance they hope for :

- Detailed reporting: Methods and data would be more nuanced, with a focus on estimates and their uncertainties, including the interval limits.

- No reliance on significance tests: P values would be reported precisely (e.g., P = 0.021 or P = 0.13) without labels like stars or letters to indicate statistical significance and not as binary result (P < 0.05 or P > 0.05).

- Better decision-making: Results wouldn’t be judged or published based on statistical cutoffs.

Retiring statistical significance isn’t a perfect solution. While it will reduce many bad practices, but it may create new ones, we must stay vigilant for misuse. Eliminating rigid categorization will reduce overconfident claims, false “no difference” conclusions, and misleading claims of “replication failure” when studies are actually compatible. Misusing statistical significance has caused harm to science and its users. P values and intervals are useful tools, but it’s time to move past statistical significance.

References

-

M. Schmidt, C.F. Christiansen, F. Mehnert, K.J. Rothman, H.T. Sørensen. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: population based case-control study. BMJ, 343 (2011), p. d3450 ↩

-

T.-F. Chao, C.-J. Liu, S.-J. Chen, K.-L. Wang, Y.-J. Lin, S.-L. Chang, et al. The association between the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and atrial fibrillation: a nationwide case–control study. Int J Cardiol, 168 (2013), pp. 312-316 ↩

-

Morten Schmidt, Kenneth J. Rothman. Mistaken inference caused by reliance on and misinterpretation of a significance test, International Journal of Cardiology, Volume 177, Issue 3, 2014, Pages 1089-1090, ISSN 0167-5273, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.205. ↩