ZipIt! Merging models from different tasks without training

Highlights

- ZipIt is a method to combine models with different initializations without any additional training required.

- Contrary to previously, it also works when the models have been trained on different tasks, allowing to create one multi-task model from two distinct models.

- The code associated with the paper is available on the official GitHub repository

Introduction

A large field of research in computer vision and representation learning is dedicated to the fusion of models. It has already been shown that when several models’ weights lie in the same loss basin, typically multiple models finetuned from the same initialization, averaging the weights of all the models produce an even better model1 (see review post here). It is even possible to leverage the invariance of most models to weights’ permutation to average models obtained from distinct initializations2. However, some methods require additional training and no work have tried to merge models trained on different tasks. With ZipIt, the authors propose a method to combine weights from two or more models trained on different tasks. They define a zip operation which allows to combine the weights of several models based on the similarity between output features at each layer of the network (Figure 1).

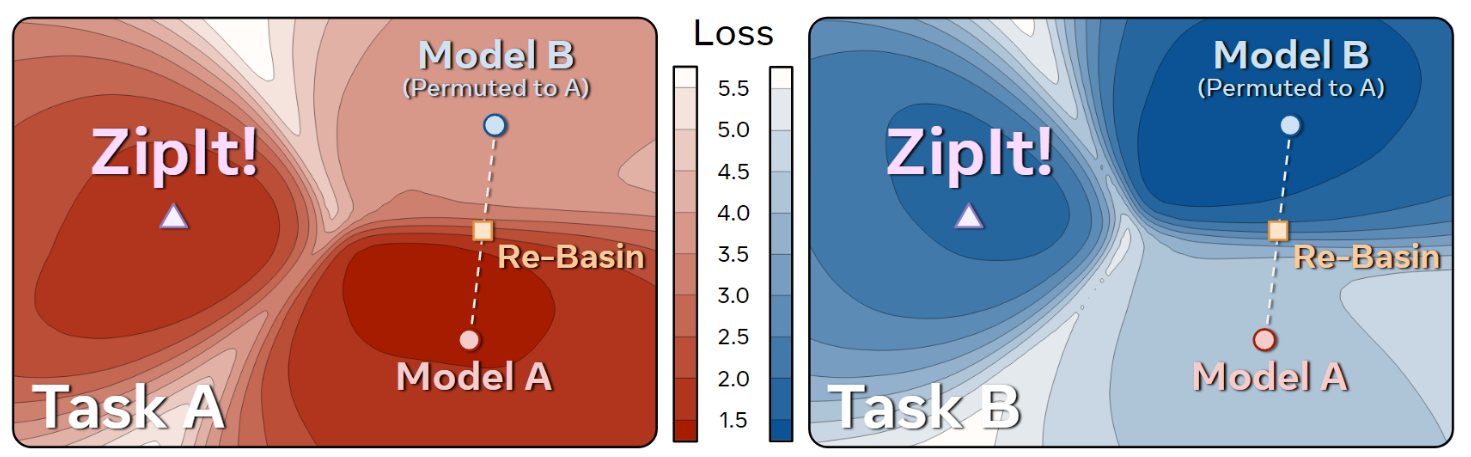

Figure 1. Overview of ZipIt compared to related previous works.

The main methods which have successfully perfomed model averaging leverage the fact that two models finetuned from the same initialization lie in the same loss basin, or can be permuted to lie in the same basin. However, this assumption is only true when considering models trained on the same task. When it is not the case, any interpolation between the weights of the models will result in a sub-optimal model (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Task loss landscapes.

Merge models with ZipIt

Let’s consider the linear layer \(L_i\) of a neural network with parameters \(W_i \in \mathbb{R}^{n_i \times m_i}\) and \(b_i \in \mathbb{R}^{n_i}\). Given input features \(x \in \mathcal{R}^{m_i}\), the output features \(f_i \in \mathbb{R}^{n_i}\) returned by the layer is given by :

\[f_i = L_i(x) = W_i x + b_i\]The goal is to take the layer \(L_i^A\) from a model A and \(L_i^B\) from a model B and merge them into a layer \(L_i^{*}\) such that the resulting output features preserve the most information from models A and B.

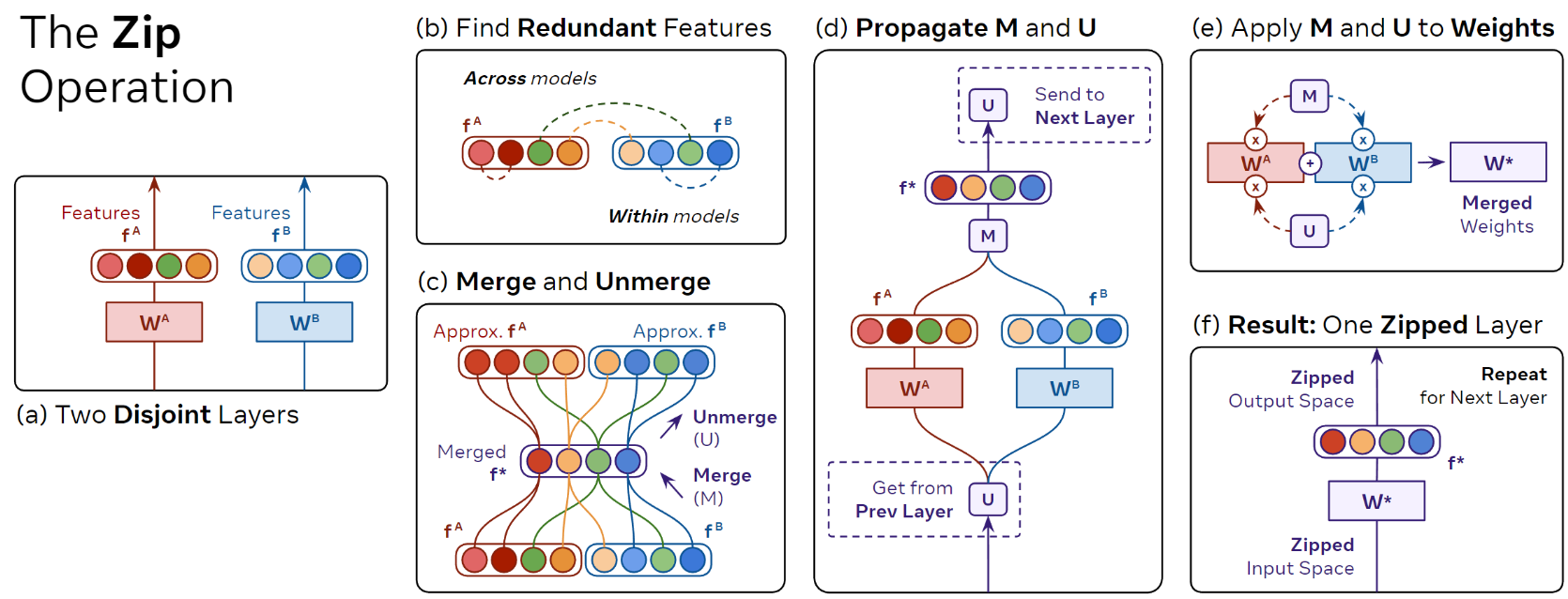

Previous methods only considered merging features across models, while ZipIt also consider merging information within each model (Figure 3).

Figure 3. How ZipIt merges layers.

The merging operation

- Concatenate features from the two layers : \(f_i^A \mathbin\Vert f_i^B\)

- Find \(n_i\) pairs of features that match the most. This can be done with bipartite matching algorithm, but since it is more costly, a greedy approach is prefered. It consists in iterativaly matching feature with the highest correlation without replacement.

- Merge paired features by averaging them : \(f_i^{*} = M_i (f_i^A \mathbin\Vert f_i^B)\) where \(M_i \in \mathbb{R}^{n_i \times 2 n_i}\) is the merge matrix. If the nth match is between indices \(s, t \in \{ 1,...2 n_i\}\) then the nth row of \(M_i\) is the average of columns \(s\) and \(t\) and 0 elsewhere.

Impact on the next layer

- After merging features in one layer, the new features \(f_i^{*}\) are incompatible with the next layers of the network.

- They define un unmerging operation which approximates the features : \(U_i f_i \approx f_i^A \mathbin\Vert f_i^B\), where \(U_i\) is the pseudo inverse of \(M_i\)

- The next layers can thus be evaluated with the merge features via : \(f_{i+1}^A \approx L_{i+1}^A (U_i^A f_i^{*})\)

- The final Zip operation is defined by : \(W_i^{*} = M_i^A W_i^A U_{i-1}^A + M_i^B W_i^B U_{i-1}^B\)

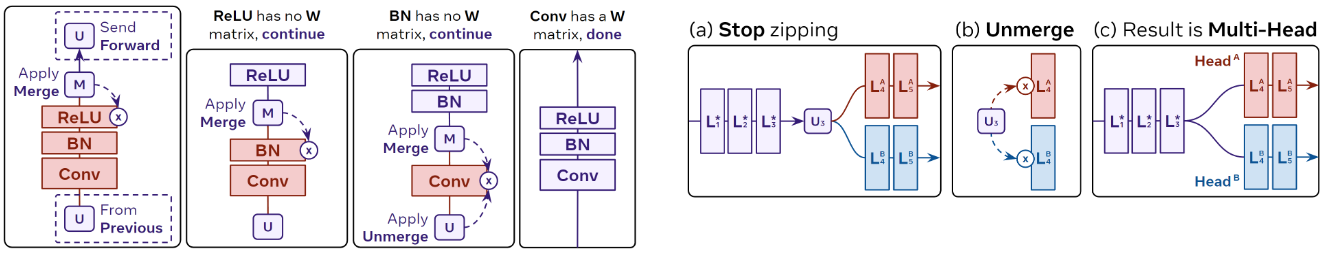

Propagation and partial zip

- Most recent neural networks are not only made with linear layers but are usually a concatenation of more complex blocks, containing for instance activation functions, normalization layers, or skip connections.

- The authors define in more details in an appendix how to apply their method to these layers.

- When two models have been trained on different tasks, their output spaces can be incompatible, or the merging if the last layers may results in a large drop in performance. With their framework, it is possible to zip layers up to a specific layer of the network and keep the ends of the original networks.

Figure 4. Zip propagation (left) and partial zip (right).

Results

The authors evaluate their merging method on different setups with increasing levels of difficulty, from merging models trained on the same datasets and label sets to different datasets and label sets

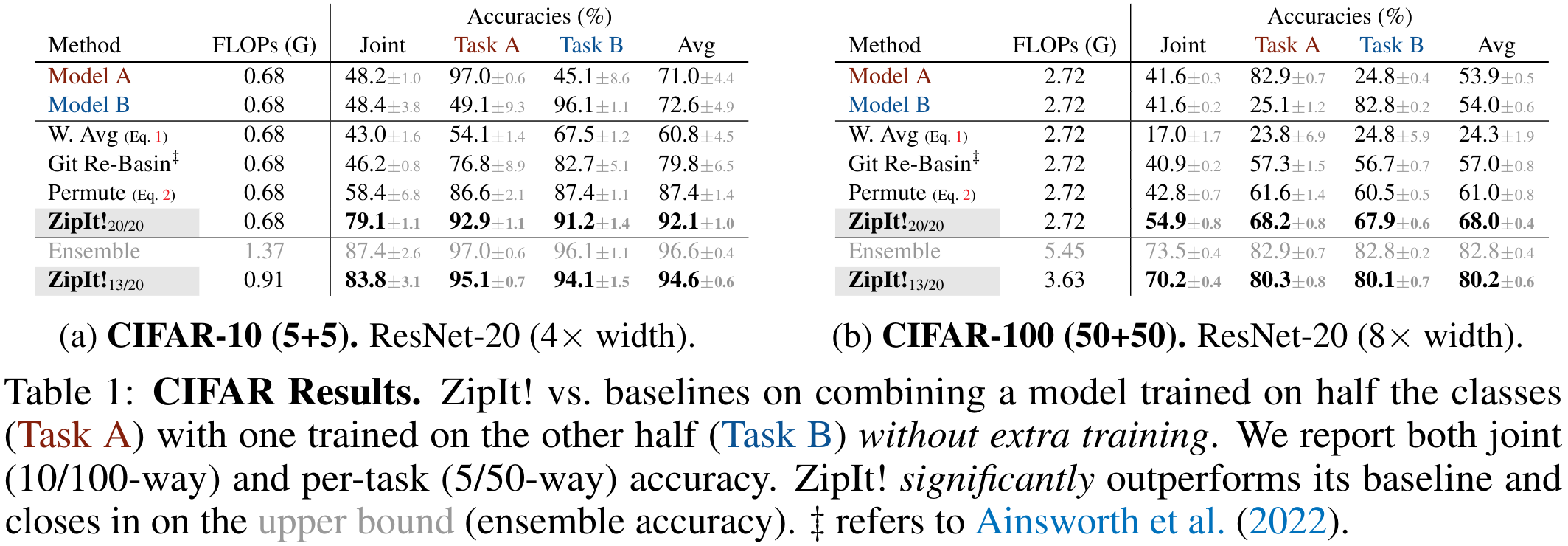

CIFAR-10 (5+5) and CIFAR-100 (50+50)

- They trained 5 pairs of ResNet-20 from scratch with different initializations on disjoints halves of CIFAR-10 classes.

- They merged models with weights average, Git Re-Basin, Permute or ZipIt methods

- They report accuracies of each model on the first 5 classes, the other 5 classes, the average on the previous two accuracies and the joint classification (10 classes). The metrics are averaged on the 5 pairs of models

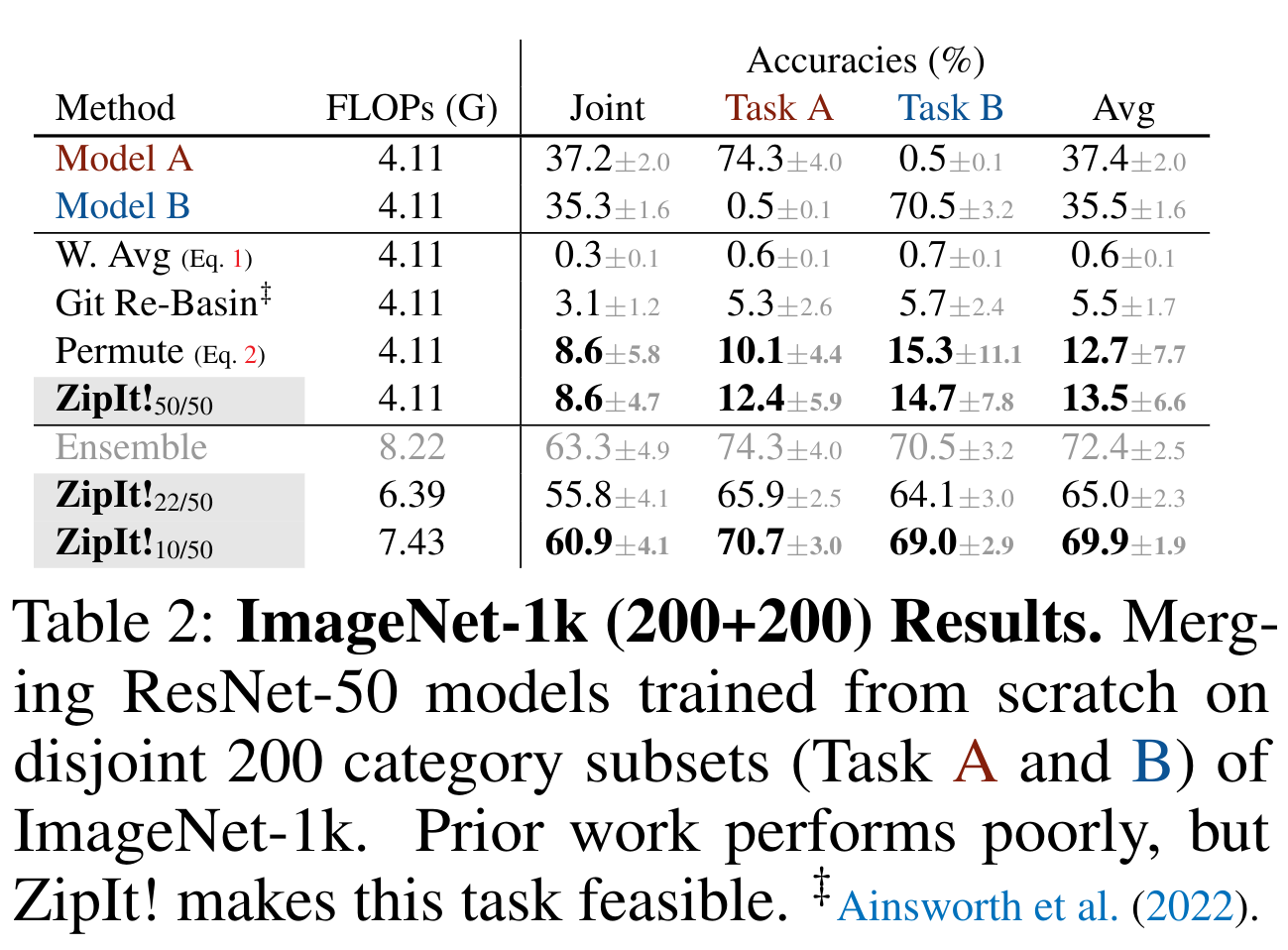

IMAGENET-1K (200+200)

- The idea of this experiment is the same except that the setup is much harder as the models are trained on 200 disjoint classes

- To be more precise, they trained 5 ResNet-50 models initialized differently on disjoint 200 class subsets of ImageNet-1K.

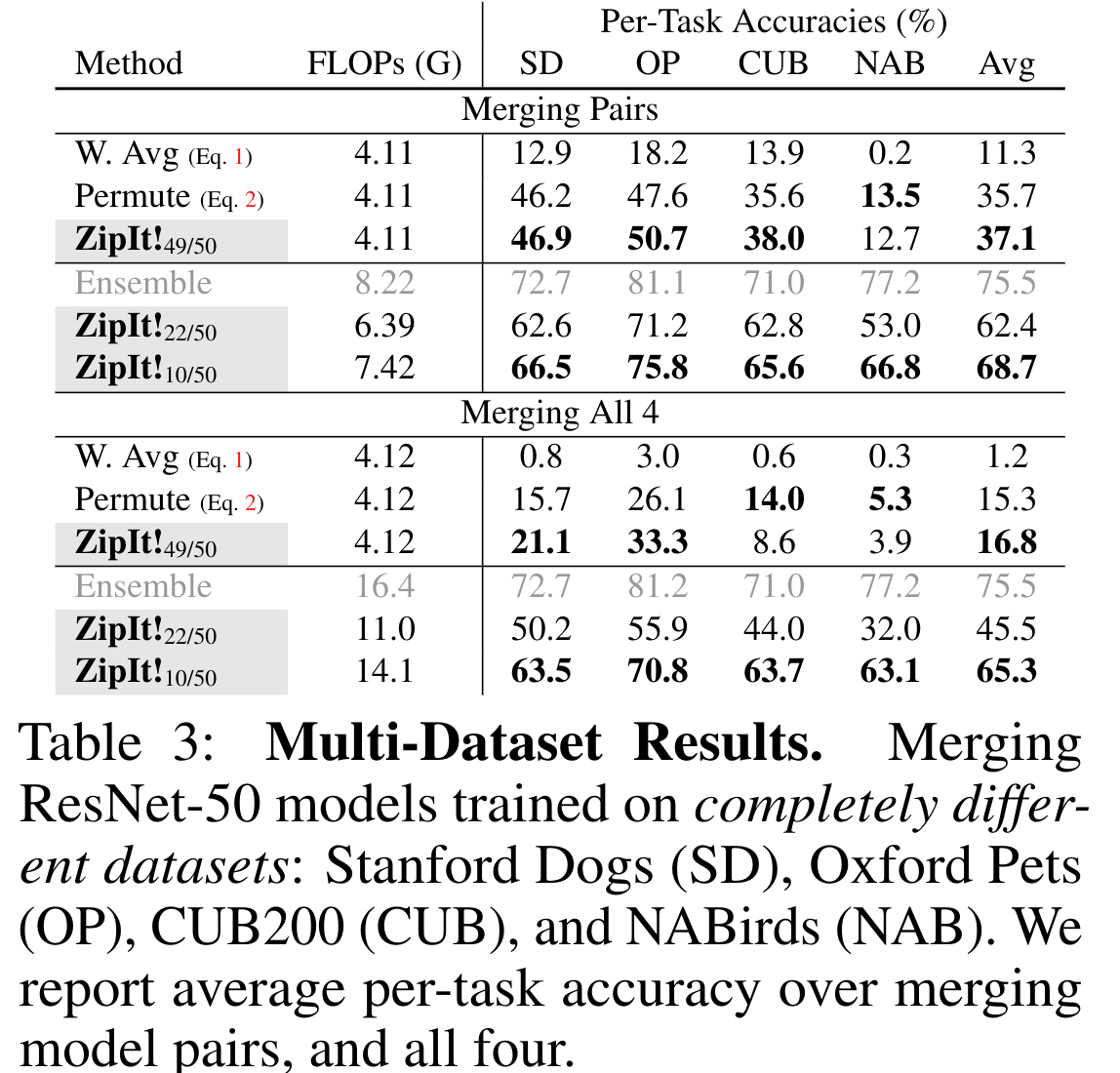

Multi-dataset merging

- The last experiments are done on the most difficult setup, when models are trained on different datasets.

- In the first experiment, 4 classification datasets are considered : Stanford Dogs, Oxford Pets, CUB200 and NABirds

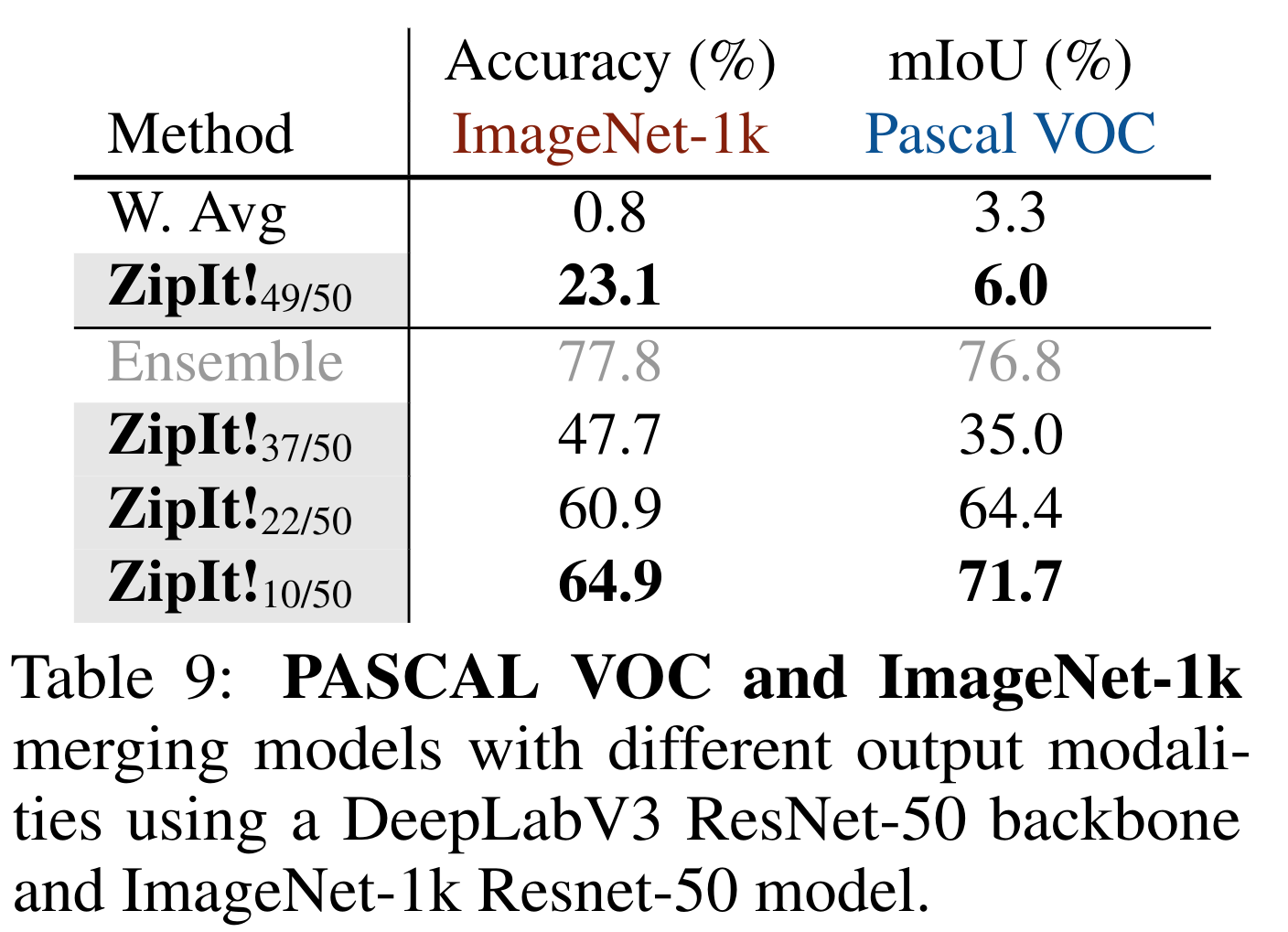

- In the second experiment, they authors merge ResNet-50 backbones of a DeeplabV3 segmentation model trained on Pascal VOC with a ResNet-50 trained on ImageNet-1k (classification)

Editorial opinion

Although the task the authors propose to address can seem a little convoluted and without direct application, I think that merging model weights trained on different datasets or even tasks may have applications in medical imaging and inspire methods to address problems of domain adaptation, generalizability, or even for foundation models.

References

-

Mitchell Wortsman, Gabriel Ilharco, Samir Ya Gadre, et al. Model soups: averaging weights of multiple fine-tuned models improves accuracy without increasing inference time, ICML 2022. ↩

-

Samuel K Ainsworth, Jonathan Hayase, and Siddhartha Srinivasa. Git re-basin: Merging models modulo permutation symmetries. ↩